by Isidor Saslav

(Swans - April 9, 2007) To judge from the etymology of the Italian names of our modern string instruments the 'cello was the last to appear on the scene during the process of those instruments' invention in Italy 500 years ago. Surprisingly enough, in view of musicians' propensity down through the centuries, even today, to joke about its practitioners, the viola seems to have come first (Spanish=vihuela), since the Italian name for the smallest member of the family is violino or "little viola"; in English, the "violin." Along with the violino came the violone or "big viola," what we call the "doublebass."

Or what we would call the doublebass if that instrument had actually stuck around. The ancient doublebass carried the shape of the viola/violin but proved too large for practical use. What we now usually call and know as the doublebass is actually a descendant, in shape and size at least, of the gamba family. The gamba family existed for centuries beside the violin family. Gambas were strung in a different way, and their members also came in various sizes. But by the end of the 18th century these instruments' watery and insubstantial tone had relegated them to the curio cabinet of the fading rococo, only to be resurrected in our own day for period performances. But the largest stand-on-the-floor member of the family, with its cutaway sloping upper back and drooping shoulders, proved favorable for evolving into the modern doublebass.

But during the days when the violin-shaped version held (or stood on) the floor, its unwieldy size must have stimulated the creation of a smaller model, the violoncello or "little violone." (Thomas Jefferson's home "Monticello" means "little mountain" and its final two syllables ought rightfully to be pronounced like the musical instrument, "chello." But we usually get the barbarous "sello" instead.) But the entire long word "violoncello" proved to be as unwieldy as the object from which it originally derived and was thus abbreviated to " 'cello" (as in the title of this article), complete with apostrophe for the dropped part of the word. Nowadays, we English speakers have lost the sense of the abbreviation and the instrument usually comes out as plain "cello."

Down through the musical centuries practitioners of the violin proved to be earlier on the scene and more numerous and glamorous (Corelli, Tartini, Viotti, Paganini, etc.) than their cello-playing colleagues (Boccherini, Piatti, Servais, Duport, Popper, Casals, etc.) It was only in the latter part of the 18th century that the cello virtuoso Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805) was able to help launch the cello as a solo instrument with his numerous and attractive compositions; while the violin had already been prominent as a solo instrument for 100 years before. (Leopold, Wolfgang Mozart's father, told his son that he could have been the finest violinist in Europe if he'd only stuck to it.)

In the course of the 19th century, when the cello was just getting traction as a solo instrument, there appeared on one of those fascinating byways of music history still another virtuoso cellist whose cellistic reputation was later to be eclipsed by his even more stellar success as a composer, Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880), later to become known as "the Mozart of the boulevards." (Two further personalities in this category are the afore-mentioned Italian Luigi Boccherini, and the later Irish/German/American Victor Herbert [1859-1924].)

Jacques (actually "Jacob") Offenbach had resettled early in his career from his native Offenbach-am-Main near Frankfurt to Paris, where he became a prominent and lead cellist in various orchestras. In those pre-boulevard days Offenbach's cellistic compositions appeared by the dozens both for artists and amateurs in the form of methods, études, opera paraphrases, concertos, etc. For the most part Offenbach's cello works have fallen into oblivion while a selected few of his operas and operettas have carried his name triumphantly into the present (Orpheus in the Underworld, Tales of Hoffmann, La Perichole, etc.).

In recent years it has been the ambition of orchestral principal, chamber, and concert cellist, and faculty member at Northwest Louisiana University in Natchitoches, Paul Christopher, to rescue the works of his cellistic forebear from such undeserved oblivion. Along with his cello colleague Ruth Drummond the duo has recorded on a 2-CD set the world premiere recording of Offenbach's complete Méthode, a series of two-cello works, from easy to virtuose, meant to guide the aspiring young cellist on his or her way to cellistic mastery.

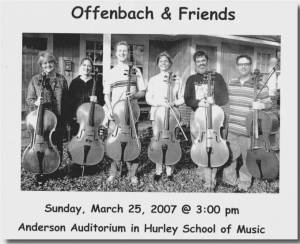

But not content with this one aspect of Offenbach's cello compositional career, Christopher has scoured libraries all over the world to re-collect more examples of the composer's early career as cellist and composer for the cello. Some of these efforts were presented by Christopher and his colleagues at Centenary College in Shreveport, Louisiana, on March 25th of this year. The group of six cellists (one doubling on piano) presented a concert that came as close to unique as one comes across in modern chamber music concert life, where repertoire is usually devoted to the oft-repeated tried and true.

This particular concert was devoted to Offenbach the composer of cello works related to the opera, that most popular of Parisian genres. In many countries "paraphrases," "fantasies," "reminiscences," "variations," etc. on operatic themes poured forth during the 18th and 19th century from dozens of composers to make accessible to the music-buying public in those pre-recording, pre-radio days some of the great tunes they had just heard or were about to hear when they visited the opera house. The public could then perform these works, if arranged with sufficient simplicity, in the privacy of their own homes.

Perhaps the most celebrated of the composers of this genre was the Europe-conquering piano virtuoso Franz Liszt (1811-1886), whose paraphrase, to name but one, on themes from Mozart's Don Giovanni, is still popular with pianists today. The virtuoso violinist-composers too had their entrants in the field: Henryk Wieniawski (1835-1880) with his Fantasy on themes from Gounod's Faust, or Pablo de Sarasate with his even more celebrated Carmen Fantasy, after Bizet, still in violinists' repertoire today. Even in the 20th century the genre persisted: violinist-composer Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962) arranged themes from Rimsky-Korsakov's The Golden Cockerel and Hollywood composer Franz Waxman (1906-67) added still another Carmen Fantasy to Jascha Heifetz's repertoire.

So over the centuries, pianists, violinists, and other instrumentalists have seen their own instrument's contribution to the genre. But what we heard on Christopher's concert was the highly unusual genre of such works composed or arranged for the cello. Perhaps some of the other 19th-century cellists mentioned above also composed in this genre but I don't know of any examples at the moment, so the concert we heard was indeed revelatory.

Within the unusualness of the concert itself the first piece performed displayed an even more unusual genre, an arrangement of operatic themes for one solo string instrument, the cello, without piano accompaniment. If such an arrangement exists for either violin, viola, or doublebass I have yet to hear about it. The opera chosen by Offenbach was Donizetti's Anna Bolena (1830), which was, as Christopher explained to the audience, Donizetti's first big hit. The various sections and arias simply followed one another in their cello arrangement without Offenbach adding anything further of his own composition. This method of arrangement was in itself highly unusual, the arranger usually adding material of his own to flesh things out. Christopher performed this work, Mélodies de "Anna Bolena" de Donizetti, as prescribed, unaided, with his usual panache, sincerity, and flair.

Offenbach's next "Fantasie" on themes from Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro, followed more customary lines. The expected piano accompaniment was ably supplied by Kristina Vaska-Haas, who, performing on her more usual instrument the cello, was to join the cello ensemble following intermission. Between the three selected arias, Cherubino's Voi Che Sapete and Figaro's Non Piu Andrai from act one, followed by the Letter Duet from act three, Offenbach added transition music of his own composition as well as similar music as coda to round the work off.

But by far the pièce de résistance of this operatically-inspired concert was the work that closed the concert after intermission, Reminiscences of themes from Robert le Diable of Giacomo Meyerbeer (originally "Jacob Meyer-Beer"; 1791-1864) for an ensemble of six cellists. Offenbach wrote the work in the 1850s, two decades after the opera's highly successful premier in 1831. He gave himself the solo lead, often in the highest register, with the other five parts meant to be played by his prominent colleagues in the Parisian orchestral world of that day. (Offenbach listed them by name in his autograph, a copy of which Christopher had acquired, and which names he read to the audience.) As the work progressed, each of these colleagues got to present at least one beautiful Meyerbeerean melody as a soloist accompanied by his/her other five colleagues. The Shreveport ensemble consisted of, besides Christopher, Drummond, and Vaska-Haas, other cellists of the Shreveport and Longview (Texas) Symphonies, David Jankowski, Claudia Sullivan, and David Pennywell. They all seemed to enjoy, in their excellent performances, the operatic melodrama and color supplied by both composer, Meyerbeer, and arranger, Offenbach.

The opera itself, like Meyerbeer's other Parisian grand operas, Le Prophète, Les Huguenots, L'Africaine, etc., is a rarity on the operatic stages of today, despite those operas' incredible popularity in their own time. As Christopher outlined the plot to the audience, a story filled with temptations by the devil and eternal faithfulness by a heroine, the work seemed an obvious predecessor and inspiration both for Wagner's The Flying Dutchman (1843) and Gounod's Faust (1859). Indeed, as the performers played a certain section its melody started out note for note as a prominent moment in the Dutchman's opening aria Nochmals Verstrichen Sind Sieben Jahre ("Again Seven Years Have Gone By"), Wenn Alle Tote Auferstehen ("When All the Dead Are Resurrected").

As this triumphant concert came to a close I couldn't help but notice in the audience Centenary College's violin faculty Laura Crawford and her highly talented and prize-winning teenage cello-playing son. It turns out that Laura's family may actually be descended from the illustrious 19th-century cellist, David Popper. Popper too enjoyed composing for multiple cellos. His Requiem for Three Cellos is still a staple of the repertoire and performed by cellists everywhere. If the relationship to the forebear is genuine then certainly the cello genes are flowing through to the youngest generation.

This whole concert would be a worthy candidate to add to the performances featured at those national and international cello congresses held in far-flung parts of the world every few years. I'm sure most of these congress's attenders have never heard any of these works before. Like similar congresses held for practitioners of the viola the congress phenomenon itself testifies to the performers on these instruments feeling the need, subliminally defensive I think, to assert themselves as an exclusive club against the performers on their more glamorous instrumental family member, the violin. (Or at least, violinists like to think it so.) Violinists don't usually feel the need to get together separately as an exclusive group every few years to re-establish their credentials and identity since they are so ubiquitous anyway.

The phenomenon of simultaneous performers on a single instrument, as exemplified by Offenbach's 6-cello ensemble, was more prominent among pianists back in the 19th century than it is today. Liszt's Hexameron (1837), meant to be played by himself and five other famous colleagues, was followed by the American Louis Moreau Gottschalk's (1829-1869) 14-piano ensemble performing Wagner's March from Tannhaueser during one of Gottschalk's American cross-country tours in the 1860s. In the 20th century the First Piano Quartet, led by Leonid Hambro continued this tradition.

On the cello this tradition is carried on at those congresses mentioned above. A specialist and practitioner in this area is cellist Laszlo Varga, former principal cellist of the New York Philharmonic and the Chautauqua Symphony and former faculty member at the San Francisco Conservatory and the University of Houston. Varga's cello groups perform his own arrangements, of which there are many. I once heard Varga and his group in a concert that featured his own arrangement of Bach's Chaconne for eight cellos.

As if one concert celebrating the cello were not enough for one day, on that same March 25th, over 100 miles away in Nacogdoches, Texas, home to Stephen F. Austin State University, was performed a 2-concert cycle featuring all of Beethoven's works for cello and piano, consisting of five sonatas and three sets of variations. The performer and instigator of this Bayreuth-type festival was faculty member cellist Evgeny Raychev, originally from Bulgaria, whose collaborator at the keyboard was Kae Hosoda-Ayer. And since most two-instrument sonatas in those 18th century days were published as "sonatas for the pianoforte" with "accompaniment" of whatever other instrument might be involved, the services of an accomplished pianist are usually very necessary. And indeed Raychev was ably served by Ayer's command of Beethoven's virtuose piano parts, written originally by the 26-year-old composer/pianist for himself to perform. Raychev had chosen that particular date for his festival because the following date, March 26th, in 1827, was the actual death date of the composer.

Beethoven's chamber works for cello extend over some 20 years, 1796-1815, and Raychev pointed out to the audience that stylistically they cover more ground than the 10 violin sonatas. Nine of the ten violin works were composed from 1798-1803 and only the 10th, from 1812, represents the composer's later style. The cello works are unusual in other ways as well. Among the five sonatas, as Raychev pointed out, there is only one fully-fledged slow movement, the third movement of the final sonata, Op. 102, No. 2, in D Major. The slow parts of the other sonatas are confined exclusively to introductions to fast movements. Such slow introductions are a rarity among the violin sonatas, the famous Kreutzer Sonata of 1803, Op. 47, being the only example, while in the cello sonatas they are the norm. Both the two twin sonatas of Op 5, Nos. 1 and 2, of 1796 have them, as well as the Opus 102 No. 1, in C Major from 1815. Indeed the slow introduction in the latter sonata becomes vital to the work's overall structure when it is re-quoted just before the end of the finale. These introductions, very long and pensive, add grandness and sweep to the sonatas that feature them and help make the cello sonatas something of a class by themselves.

In these concerts too the operatic arrangement was not far away. Beethoven's three contributions to the genre consisted of sets of variations on a theme from Handel's Judas Maccabeus, Hail the Conquering Hero, and on two different arias from Mozart's The Magic Flute, Papageno's Ein Maedchen oder Weibchen and the Papageno/Pamina duet, Bei Maenner Welche Liebe Fuehlen, both from act one. In Beethoven's other chamber music variations on other popular opera tunes of the day make several appearances, such as in the early set of violin/piano variations on Si Vuol Ballare, Figaro's aria in the first act of Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro.

The order in which Raychev presented these works was on the first concert to present the first two sonatas on the first half and the Judas Maccabeus variations and the third sonata, Op. 69 in A Major, the only representative among the cello sonatas of Beethoven's middle period, on the second half to conclude the concert. On the second program, after dinner, during each half a Mozart variation set was paired with one sonata from the Op. 102 set.

Raychev, besides being an excellent performer of determination and emotion, is a serious scholar as well. He and his wife, SFA violin faculty member Jennifer Dalmas, have established a list of works written for their familial combination, cello and violin. The couple revived and performed, a few seasons back, the little-known double concerto for violin, cello, and orchestra (1910) by Saint-Saëns, which the composer entitled La Muse et le Poète.

So all in all it was a great day for the cello (or " 'cello"). With able and talented scholar-performers like Christopher and Raychev in its service new vistas in its repertoire will continue to open and be revealed to us, its listeners and admirers.

Please keep Swans flying. help us financially. Thank you.